We are well aware that driving our cars around, perhaps in pre-Covid-19 times, can have negative effects on the environment by increasing the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, reducing air quality, and increasing the likelihood of pollution in waterways; all of which can have significant effects on human health, but what about impacts on biodiversity? As part of my recent PhD research at the University of Sussex, jointly funded by VWT, I carried out investigations into the effect of traffic noise on the activity of bats.

Motorway traffic in Devon. Photo: ©Domhnall Finch

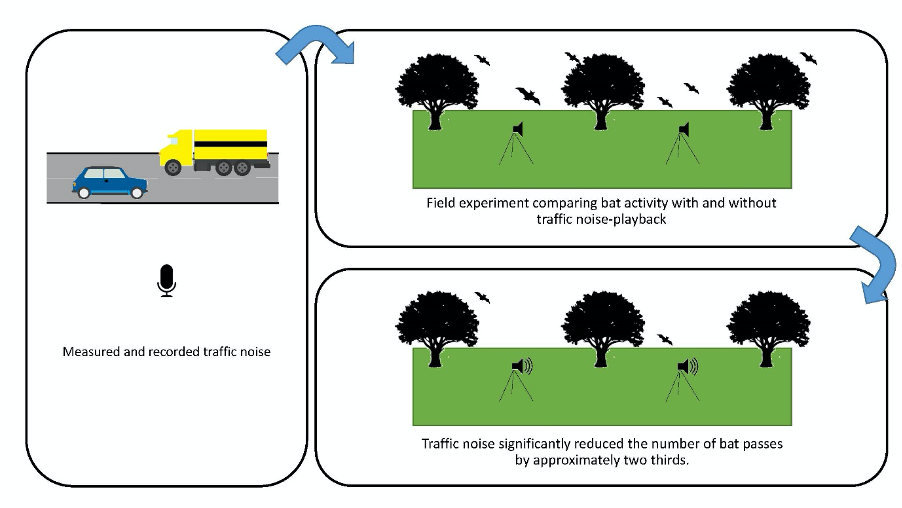

In areas previously undisturbed by heavy traffic noise, we used a phantom road playback experiment to replay traffic noise through speakers along hedgerows and treelines to mimic the effect of passing cars on bat species, as we monitored potential changes in their activity levels. This two-year study initially examined the effects of both the sonic and ultrasonic spectrums of traffic noise together.

Traffic noise has a significant impact on bat activity

Our results demonstrated that traffic noise can cause a reduction in total bat activity by approximately two thirds. This negative impact was also recorded 20m away from the source of the traffic noise. These effects were seen across a broad spectrum of bat species that have varied foraging strategies and frequencies at which they echolocate, including the greater horseshoe bat, common and soprano pipistrelles, noctule and the genus Myotis, which includes Bechstein’s bat and Daubenton’s bat. These effects were not just limited to the number of bat passes; we also saw a reduction in the number of feeding buzzes – calls which are emitted by bats immediately before they capture their prey items – for both common and soprano pipistrelles during the experiment.

The greater horseshoe bat is just one of the bat species shown to be affected by traffic noise. Photo: ©Frank Greenaway

When the sonic and ultrasonic spectrums were played on separate nights, we demonstrated that it is the sonic spectrum that has the highest impact on bat activity. These results suggest that traffic noise isn’t jamming or masking bat echolocation calls but rather it is causing an avoidance behaviour in bats.

Further research is required though to identify effective mitigation strategies, to delineate the zone of influence of road noise, and to assess whether there is any habituation over time. However, as many bats are of high conservation concern, Environmental Impact Assessments need to consider the potential effects of road noise on habitat quality, landscape connectivity, and population viability. These effects need to be considered in combination to those of street lighting, collision and direct habitat loss and prioritised accordingly. These assessments are not just important when new roads are due to be built but also need to be considered if there is to be an increase in the volume of vehicles using it (eg through road widening schemes).

Dr Domhnall Finch