Generally, I quietly work behind the administrative scenes and am known more for my style (as in writing guidelines) than my natural science. However, I was drawn to the work of Vincent Wildlife Trust because of my fondness – call it obsession – for all-things Mustelidae.

In January 1977, a second-year (Yr 8) form teacher at Boscombe Convent School presented her pupils with a challenge. We were each to research and compile a project on any mammal of our choosing to be submitted at the end of the term. Many of my peers opted for majestic blue whales, cute red squirrels, or menacing African lions.

Having long aspired to become a river otter when I grew up, my thoughts immediately led me to the water. But then I visualised the iconic badger, curiously cloaked in a folk belief that asserted that old brock had shorter legs on the left side for walking around hills. And then I remembered stoats, whose flayed winter coats featured all-too often in school history books. Pulled in several directions, I decided to cover them all, from the ubiquitous striped skunk, to the wily ratel, the lesser-familiar grison, tayra, quique, and zorilla, and to the emblematic black-footed ferret.

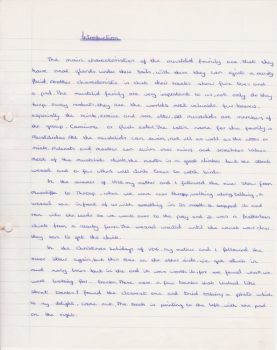

Cover page and first page of Introduction

I read everything I could find from classic novels such as Ring of Bright Water and Tarka the Otter; autobiographic works by Philip Wayre and Phil Drabble. I would camp out at the local library ploughing through encyclopaedias and nature books. I remember waiting for what seemed an age for Earnest Neal’s seminal book The Badger to arrive.

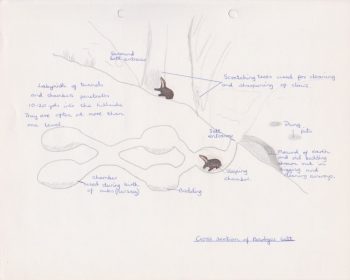

Diagram of badger sett

My fieldwork included dragging my family to a plethora of wildlife centres, and somehow I wangled a trip to The Otter Trust in Bungay where I met Spade, the otter who starred as Tarka in the film, and in my arms I held Mouse, the elderly otter who played Tarka’s mother.

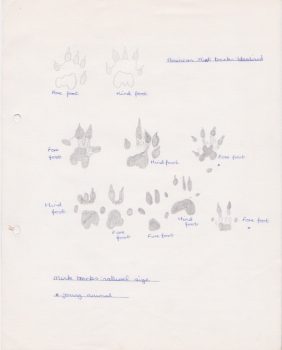

One misty spring morning, I photographed stoat tracks along the bank of the River Stour, and shortly afterwards I startled a weasel carrying a freshly-caught chick, stolen from a nearby farm. The weasel dropped its prey and scarpered, only to return to retrieve it once I had moved on.

Page from Chapter 1 showing photograph of stoat track

American mink tracks

Within a few months I had accumulated a thick folder of hand-written reports of Mustelidae worldwide, with supplementary images, sketches, photographs, cuttings, and responses from the many experts to whom I wrote: the Forestry Commission, water authorities, fisheries and zoos. I formed an ongoing correspondence with staff members of the Nature Conservancy Council, who kindly mailed me all the latest publications on badger gates. To this day, I am amazed and grateful to everyone who replied to a 12 year-old school girl’s inquiries, and who generously supplied empirical data, scientific details, bibliographic advice and the latest edition of booklets.

Letter from C.R. Tubbs, Nature Conservancy Council, January 1977

Response from G.W. Lightfoot, Wessex Water Authority, February 1977

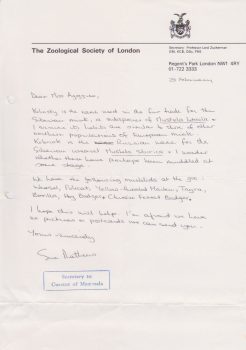

Information sent by Sue Matthews, The Zoological Society of London, February 1977

Up until that point, my presence at school had been unremarkable, but once my completed project made the staff-room rounds, teachers from other years sought me out to congratulate me on my magnum opus. One rather imposing teacher cornered me on the stairs and asked me what I wanted to be when I grew up, and sensing that my desire to become an otter might not go over too well, I suggested I might like to become a vet. Nonsense, she swiftly replied, you’re too small to stick your arm up a cow’s behind. After that encounter, I focused my studies on human history.

However, my mustelid fascination has stayed with me, and I feel privileged to have enjoyed many a wild encounter in various regions of the world, most notably during my time in Alaska. I am honoured to play some small part in VWT’s conservation strategy for many members of this enigmatic species.

Dr Maria Teresa (Mabli) Agozzino, Communications Assistant

All images: ©Maria Teresa Agozzino