It’s 3am on a Monday morning in June 2019 and I’m perched on a box in the cold dark of a small room, grateful for the many items of branded clothing I’d been issued with when I joined Vincent Wildlife Trust (VWT). I’m wearing them all now…and still I’m cold. I’m also struggling to keep my eyes open. With their heads together and hunched over the only light in the room, which is coming from a tiny screen, I’m certain the two other people here wouldn’t notice if I close my eyes and sleep. But there’s nowhere to sleep.

Suddenly, there’s excitement as a small, rotund figure flies across the screen and comes to rest, hanging upside down and slowly swaying with ever-diminishing momentum until it stops. I’m wide awake now.

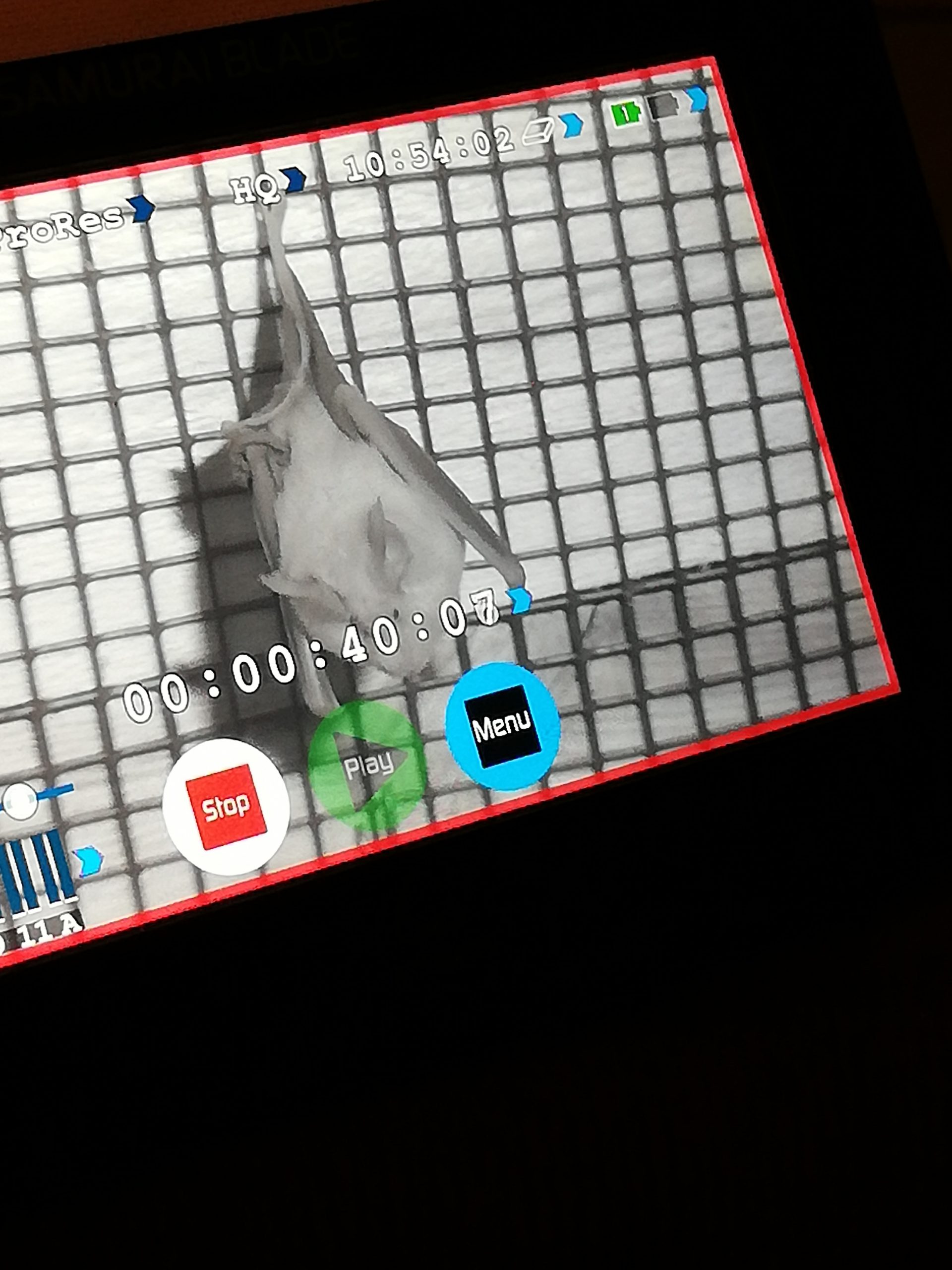

An infra-red camera in the roost, linked to a monitor on the ground floor captures life inside the roost without disturbing the bats. Photo: ©Julia Bracewell

We are in a small room at Bryanston Old Kitchens, one of VWT’s largest greater horseshoe bat roosts, watching and waiting for the bats to return from their nocturnal feeding trips and to settle into their roost. I assume that they will sleep off a night of feasting on insects. Their favourites include the cockchafer, a large crunchy beetle, and the equally chunky yellow underwing moth…but most insects unfortunate enough to miss the swift and silent wing beats of these bats will be taken.

Sadly, during the last century, the abundance and variety of insects along with suitable habitats declined drastically with changes in agricultural practices and with the increased use of pesticides. And with these losses, came the inevitable decline in greater horseshoe bats. Some estimates put it at over a 90% loss by the 1980s, leaving a sparse population of only 5,000 individuals in Britain.

With such catastrophic figures, the founder of Vincent Wildlife Trust, Vincent Weir, took the costly steps of acquiring buildings where the greater horseshoe bat was clinging on and funding research into how buildings and the surrounding habitats could be enhanced to provide maximum protection and the most appropriate conditions for the different stages of a year in the life of a bat. These sites are now managed by VWT as bat reserves to provide safe and suitable havens.

Unlike other species, horseshoe bats can’t crawl into crevices and need to have roosts with openings large enough to fly into and surfaces that they can suspend from. As with most bats, they have different habitat needs during the year: a warm, safe space for pups in a maternity roost and a cooler space for winter hibernation. And of course, a surrounding habitat that can provide them with a good supply of insects. The Old Kitchens fulfils these needs. It is an old sandstone building in the grounds of Bryanston School and was once the catering quarters for a large country house. The house has long since gone, but this building remains and now belongs to the bats.

Bryanston Old Kitchens

With me in this small space are Anita Glover, VWT’s Bat Programme Manager, and Andrew Thompson, Film Director with BBC Scotland. We are here to capture footage of the normally hidden world of a greater horseshoe bat roost for Andrew’s latest project: Inside the Bat Cave. The aim of this and a further four visits to this reserve is to spend weekly eight-hour shifts staring into the monitor and to record life inside the roost. Andrew is hoping to capture footage of a live birth during these sessions. I’m just hoping I can survive the next few weeks.

But for now, I’m captivated by the sight of this round ball – a heavily pregnant bat. We are able to peek into this unseen world of bat roosts thanks to an infra-red camera, which was installed in the roof space earlier in the year, long before the breeding season began in order to avoid disturbing the bats. The camera is linked to a small monitor on the ground floor, which we are now glued to as the bats are starting to return. Our fingers are poised to hit record and soon this single bat is joined by others as they fly in and hang in ones and twos. But sleep seems to be the last thing on their minds.

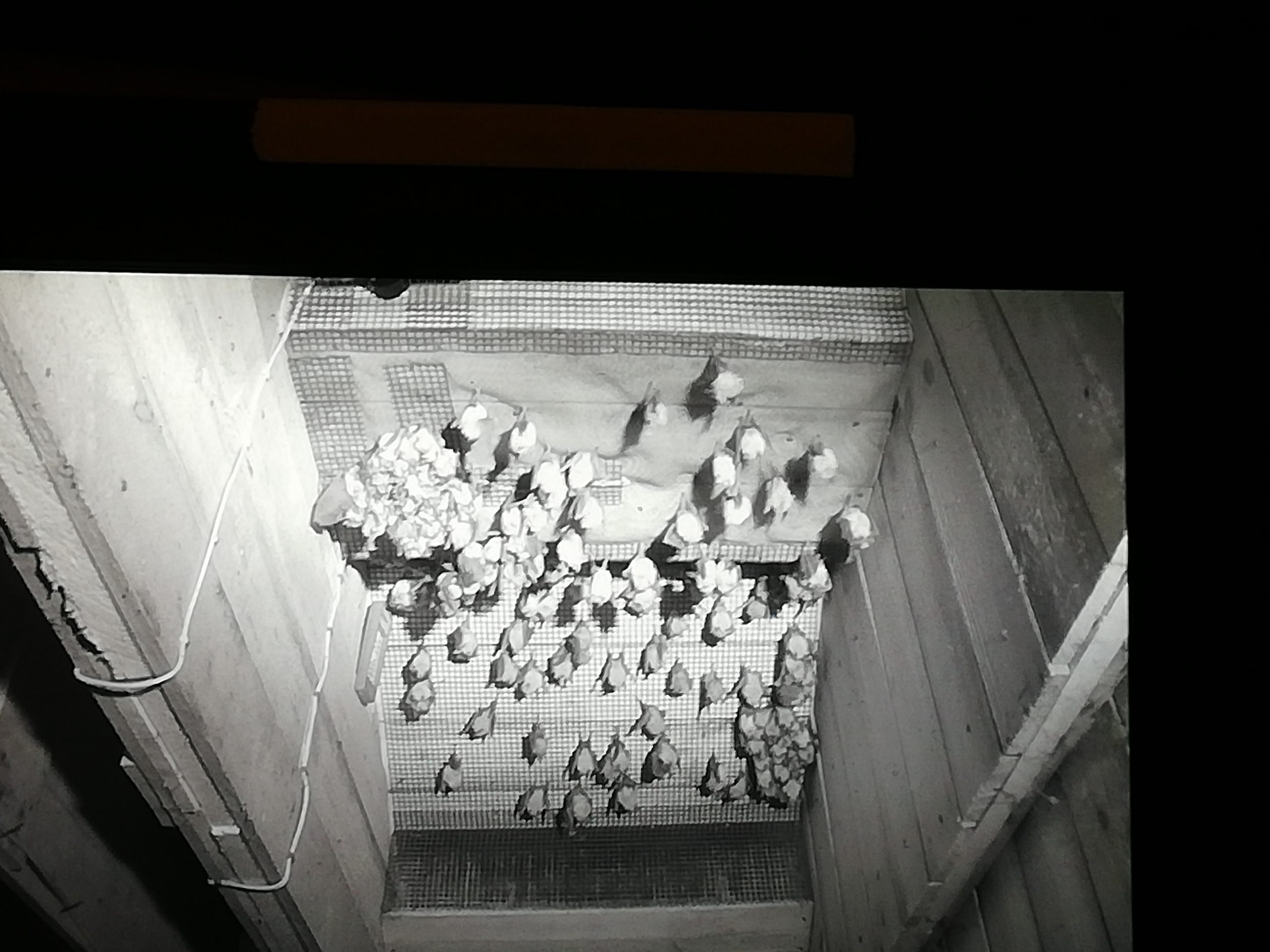

We watch these ethereal creatures of the night start the mundane task of grooming. Although I’ve seen countless animals cleaning themselves, this seems different, almost choreographed. Suspended from the ceiling mesh by the tiniest toes, they stretch out long elegant and almost translucent wings. Ballet dancers of the bat world, they sway and spin as their cleaning creates momentum. Having licked every millimetre and maybe more, this fastidious bat suddenly envelops herself in her wings and transforms into an origami kite that hangs. We move on and scan the area for other bats. While we’ve been engrossed by the cleaning, more bats have flown into this roof space, which is known as a hot box. Designed specially for maternity roosts, it is a thermostatically heated and insulated box where mothers can leave young pups at optimal temperatures for growth and survival while they go out to feed.

Screen shot from the monitor showing the hot box. Photo: ©Julia Bracewell

We carry on slowly scanning, when Anita spots something. She takes the control and zooms in on an oddly shaped bat. It’s a mother with a young pup and we can just see the tip of it clinging on, tucked beneath its mother’s folded wing cocoon. This is the first sighting this summer of a young greater horseshoe bat and is something to celebrate. Vincent’s strategy of taking on buildings and enhancing them as safe roosts seems to be paying off as the number of this species has been slowly rising – the latest estimate in 2018 is a British population of around 13,000. I’m sure he would be delighted to know that the reserves he established are now host to around 50% of this total population, with one of the roosts being home to the largest known greater horseshoe bat maternity colony in western Europe. While the majority of the British population is still found in the southwest of England and in south Wales, there are early signs that they are expanding their range into the southeast of England and north Wales. All of this is good news, but there is still much more to do in order to bring greater horseshoe bats back up to their previous population levels.

Suddenly the mother unfolds her wings and starts to clean her young pup…it is the equivalent of spit and rub as the pup is thoroughly cleaned all over, including behind the ears. Maybe in a bid to escape this attention, the pup suddenly drops down, hanging by its feet to the mother. At this stage it seems all angles and skin, and somewhat baby dragon-like as it is yet to fill out and fluff up. It starts to stretch and flap its wings, rest and then repeat. Although this youngster probably won’t start flying until August, it is already flexing muscles and preparing for independence. This vigorous movement causes the young pup to swing right round on its feet in both directions and I wonder out loud how these bats are able to cling on for so long. Anita explains that bats, like birds, have a specialised tendon locking mechanism that locks the feet into a grip with very little muscular effort. This means that the muscles are in a ‘relaxed’ state while they are hanging on.

We realise that the hotbox is getting quite crowded now with huddles of bats dotted across the ceiling. In between these huddles are individuals grooming and stretching or occasionally sidling up to each other to ‘converse’. As we zoom in on one huddle of around 15 bats, we can see that the bats are tightly packed together and seem to be finally resting until the next evening’s feeding flight…or so I thought. The whole group suddenly jolts, as if a pulse started by one travels through the whole. As we watch, it happens again and again. A regular beat. Our trance at this pulsing collective is suddenly broken as a bat flies in from the right and barges its way into the bundle. There are the inevitable moments of disgruntled fidgeting to accommodate this incomer and then the group settles once again into its rhythmic heartbeat…until one of the bats decides to leave and sets off another round of fidgeting and settling and pulsing. I realise now that my view of a bat roost as a still place of sleep has been hugely altered as we continue to scan and watch the pulsing huddles, the grooming individuals and those just stretching or flapping or fidgeting.

Screen shot from the monitor showing a greater horseshoe bat huddle in the hot box. Photo: ©Julia Bracewell

And then it is time to switch off the camera and monitor. The last hours have disappeared in minutes and, although there wasn’t a live birth to capture on camera, as I stumble out into the daylight, I feel extremely privileged to have had this peek into the hidden world of the greater horseshoe bat.

Julia Bracewell, VWT Senior Design and Communications Officer